- Home

- Sue Monk Kidd

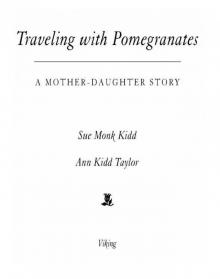

Traveling With Pomegranates Page 3

Traveling With Pomegranates Read online

Page 3

Near the peak, the steps leading up to the Propylea become clogged with people, a huge throng of multicolored fanny packs. We shuffle along, forced to take baby steps. Finally, squeezing through the colonnade, I catch a glimpse of the Parthenon glowing fluorescent in the sunlight, throwing long, symmetrical shadows, and I go a little weak in the knees.

“I think I’ll wander around for a while by myself,” I tell Mom, not wanting her to see how sad I feel all of a sudden. She gives me a look, so I add, “You know, like it suggests in the guidebook.” There’s an entire paragraph in it about the “necessity” of a moment alone to let the sight of the Parthenon break over you.

“Sure,” she says. “Good idea.” She starts to walk away, then stops, turns around. “Are you happy to be back?”

“You must be joking!” I smile at her.

All my life I’d been the quiet, happy girl. Now I’m the quiet girl pretending to be happy. Every day is an acting class.

Hurrying toward the Parthenon’s western pediment, I glance once over my shoulder and see Mom headed in the opposite direction. Who am I kidding? She’s on to me.

With surprising ease I locate the same slab of marble I sat on when I was last here. Until recently I’d kept a photograph of it on my desk. The marble is long and narrow and tilts slightly upward, reminding me, as it did then, of a surfboard that has just caught a wave.

I sit on it, feeling the coolness hit my bare legs.

Right before I left on that college study tour to Greece, my boyfriend of four years, the one I thought I would marry, called and broke up with me. Out of nowhere.

“One day you’ll find someone and he’ll be the luckiest guy in the world,” he told me. I think he intended for this to make me feel better, but come on, the luckiest guy in the world and he didn’t want to be that guy. So, when I should’ve been making big Xs on a countdown calendar, buying travel-size shampoo and watching Shirley Valentine and Zorba the Greek, I sat on the blue sofa in the apartment I shared with my best friend Laura in a state of shocked disbelief—what birds must feel after flying into windowpanes. That was followed by a period of pure heartache. I abandoned mascara and retreated into class lectures, cafeteria gossip, and the absurdly watchable Days of Our Lives that played in the student lounge, feeling my life rub against routine, against the lives of other people, but oddly disengaged from it. Laura gave me postbreakup pep talks, attempting to pull me back into the living world.

At the apex of this pathetic state, I called my mom and told her I didn’t think I wanted to go to Greece. “Why should I go halfway around the world and be lonely, when I can do that here?” I said with complete irrationality.

I couldn’t imagine tromping around Greece with my heart fractured. I didn’t mention to her that I barely knew any of the other girls who were going, which felt more than a little scary. I’d made my peace with being an introvert. It only meant that my natural inclination was to draw my “energy” from within instead of seeking it outside of myself, plus my mom was an introvert, and so were a lot of normal people. The problem was I was shy on top of that. And we all know how the world loves a shy introvert. The combination trailed after me like the cloud of dust and grunge that perpetually follows Pigpen around in the Peanuts cartoon. The only thing harder than being around forty girls was thinking up what to say to them.

Mom was sympathetic, but told me, “I know this must be hard for you, Ann, but I have a feeling you’ll look back and regret not going. Think about it, okay?”

The minute she said this, I knew it was true—I would always regret it if I didn’t go. It was so like her to hone in on the truth where I was concerned and then leave it to me to decide. Mom had never been one to offer unsolicited opinions about what I ought to do. Which is why when she did give advice, I tended to listen.

So I went.

Somewhere over the Atlantic, sitting with an entire row of seats to myself in the back of the plane, I watched as a few of the girls in our group started a party with nothing but a bag of jelly beans and a quiz out of Cosmopolitan magazine. From that moment, I thought of them as the Fun Girls.

I told myself if I couldn’t be a Fun Girl, I could at least be a Diligent Student.

When we boarded the chartered bus to Delphi, our first stop, I settled (again) in a seat to myself, spreading out maps and books and making copious notes as our Greek tour guide, Kristina, lectured. “Delphi is situated on the steep, craggy slope of Mount Parnassus. It was the navel of the world for ancient Greeks, and a pilgrimage site for thousands of years.”

Apparently people had flocked here to consult the Delphic Oracle, a priestess of Apollo who answered everyone’s most pressing questions while in a trance, or, as Kristina noted, while probably intoxicated on “fumes.”

“Like sniffing glue?” one of the Fun Girls said.

Kristina actually nodded.

Despite the source of the oracle’s prescience, she was apparently good at what she did. It was she who told Oedipus he would murder his father and marry his mother, and we all know how that turned out. I decided I would’ve lined up with the rest of the world to hear what she had to say about my future: Will anyone ever love me again? Will I ever get over my withdrawn and tentative way of being in the world? What am I supposed to do with a bachelor’s degree in history? Better yet, what am I supposed to do with my life? I didn’t have a clue.

We piled out of the bus and followed the Sacred Way that snaked up to the temple of Apollo. It was March; cold, thick vapor drooped over our heads. The entire side of the mountain was strewn with white ruins. I moved among them feeling a little spellbound. Halfway up, it began to snow. The flakes floated through the cypresses out toward the watery blue line of the mountains. I turned 360 degrees trying to take it in, and I could feel something inside of me start to open like a tiny flower. I think that’s when I stopped thinking so much about my poor, cracked heart and succumbed to the magic of Greece.

I’d been studying its history, culture, art, architecture, and myths for weeks in classrooms, but now that I was here, those subjects felt alive and vividly present. They brought into sharp focus all the life I had not lived, all the places in the world I had not yet seen, how large it all was. Being here made me feel alive and vividly present, too. There were things, it seemed, that could only happen to me in Greece.

We scrunched down in our jackets as Kristina pointed out where the words KNOW THYSELF were carved prominently into Apollo’s temple, and suddenly I had a “palm-slap to the forehead” moment. The inscription must’ve been the more ulterior meaning of the oracle: to find the answers inside oneself. What if the oracle was a metaphor for a source of knowing within?

As I treaded toward the amphitheater with the group, wondering whether I possessed my own source of self-knowledge, I had a thought which seemed to have originated from just such a place: I forfeited way too much of myself as a girlfriend.

I don’t know how I knew it to be true—and in fact, to be vital—but I did. Maybe it was because I was far from home, far from my ordinary circumstances, and more or less alone for the first time in my life, feeling like I was on an awkward first date with myself. I’d known who I was with my ex-boyfriend. I’d invested years in the girlfriend role, in the ways of accommodation, being what I thought he wanted me to be, moon to his Jupiter, quietly organizing my psychological orbits around him. But in Greece, I existed in a kind of solitude, and in this quietness I realized I’d lost my self.

In the Amalia Hotel in Delphi, I woke several times during the night, and the truth of this knowing was still there in the darkness. And there was longing there, too. For myself.

The next day, we wandered along a gravel path to a small, circular ruin known as the Tholos. Built as a temple to Athena, its shape was mysterious to archaeologists, who were still guessing what it had been used for. All forty of us reverted to whispers as we moved among its remnants.

One of the papers I’d chosen to write to fulfill the study requirements for th

e tour was about Athena. I’d become fascinated with her. I’d tended to think of her only as a soldier, but long before she was given a helmet and a spear, she had been a nurturing Goddess of fertility, wisdom, and the arts. I liked both sides of her—the wise nurturer and the fierce warrior. But what I loved most was that she was a virgin Goddess. Her virginity was about much more than the fact that she never married. It symbolized her autonomy, her ability to belong to herself. I’d included a section about this in my paper, unable to see then how I had given too much of myself away.

Standing in a lump of marble fragments, I found a plaque on which the words TEMPLE OF ATHENA were engraved in both Greek and English, and lying on top of it were two yellow wildflowers. Someone had carefully knotted the stems together. An offering to Athena. I felt sure of it. Seeing the flowers, I understood that some people still loved and revered Athena. Time moved on. The whole world moved on. Athena, and her potent meaning, had not gone anywhere.

Searching the ground, I picked up one of the millions of pebbles scattered around the site. I turned it over in my hand and began to pray for the things Athena was revered for—wisdom, self-possession, bravery.

I didn’t want anyone to notice what I was doing, and thereby become known as the Weird Girl, so I placed the tiny rock by the yellow flowers as inconspicuously as I could. Don’t ever lose yourself again, I told myself.

A short time later in the Delphi Museum, I stood mesmerized before a bronze statue from the fifth century BCE known as the Charioteer of Delphi, realistic down to his wiry eyelashes. The story goes that while a French team was clearing a village for excavation, an old Greek woman, who’d previously refused to abandon her house, dreamed of a trapped boy calling to her, “Set me free!

Set me free,” which finally convinced her to leave. When the archaeologists dug beneath the house, they found the Charioteer.

“Do you think he’s seeing anyone?” one of the Fun Girls joked, and I laughed, but I also got her point. He was gorgeous. The white of his eyes appeared alive and his mouth seemed about to break into a smile. Kristina explained that his expression depicted the first seconds after his chariot victory. He was on the cusp of elation and the anticipation of it—set in stone—was eternal. When I walked away from him, from Delphi, from the navel of the earth, I felt his voice rumbling down inside me. Set me free, set me free.

A few days later, however, when Kristina summoned all of us to a footrace on the ancient Olympic track in Olympia, all I heard was the racket of my own panicked self-consciousness. The stadium was packed with tourists. This is so juvenile. Turning to Dr. Gergel, my faculty advisor, I asked if the race was a requirement. “You’ll regret it if you don’t,” she said, smiling. Why were people always saying that to me? I lined up with the others and stared 633 feet to the end. Even with the throng around us, the world seemed to get very quiet. “You are standing exactly where the athletes in ancient times stood; you are breathing in the same space,” Kristina called out. When she blew the whistle, I ran with my whole heart. I hadn’t run like this since my brother, Bob, and I raced barefoot on the beach in South Carolina. I honestly couldn’t believe it when a girl passed me, kicking up dust with her Keds, but by then I had so surprised myself it didn’t matter. I was breathing in the same space. The first- through fourth-place winners stood on the four stone pediments where the athletes had once been crowned. I finished in second place.

Kristina placed an olive wreath on each of our heads while the rest of the group sang the American national anthem. Someone took our picture. In it, I am smiling like the Charioteer, a cluster of black olives hanging over my right eye.

Other than a couple of writing contests in my early teens, I had never won anything. Winning second felt as good as finishing first. I didn’t know I had it in me. It made me wonder what else I could do that I wasn’t aware of. I wore the Nike Air sneakers that had carried me across the finish line everywhere for a long time, and when I finally retired them, I couldn’t bring myself to throw them away.

The stirring and surprising events of the trip slowly began to unravel my old self. Strolling beneath the Lion Gate in Mycenae, teetering over a footbridge a thousand feet in the air in Meteora, eating pita and tzatziki like chips and salsa—again and again I felt the intensity of being alive, as if my destiny was pooling in around my feet. The experiences I was having seemed to be refashioning me. They were returning me to myself.

“There is a name for what happened to you,” Kristina told me at the end of the trip. “It’s called the Greek Miracle.”

On the last day, in a small shop in the Plaka, the oldest quarter in Athens, I bought a silver ring with Athena’s image carved on it, then climbed the hill to the Acropolis, where I found the slab of surfboard-shaped marble near the Parthenon. Sitting on it, I unceremoniously slid the ring onto the finger on my left hand, the one reserved for wedding rings. The ring was about Greece and staying connected to the fire this place lit in me. It was a way to be reminded of Athena’s qualities and the potential to find them in myself.

As I lingered there, an awareness that had been growing in me throughout the trip coalesced and I knew what I wanted to do with my life. I decided I would go to graduate school and study ancient Greek history.

On some level this made practical sense—I was a history major and graduate school seemed a smart choice. But it wasn’t just pragmatic. I had, by now, been swept off my feet by Greece in every way. When the idea presented itself, I felt a snap of brightness inside. Later it would remind me of the click inside a kaleidoscope when all the tumbling pieces merge suddenly into a pattern of radiance. That was my moment.

That same night, three Fun Girls and I walked blocks through the Plaka, searching for a restaurant, but all the tables at the outdoor cafés were occupied. Finally, huddling on the sidewalk, we discussed options. Should we go back to the hotel to eat? I was ready to buy gyro meat on a stick from a walk-up counter, but the Fun Girls insisted we find a sit-down restaurant. “Couldn’t we just ask a local?” one of them suggested. She nodded at a tall, dark-haired guy standing behind us. He looked about our age, his hands stuffed in his jacket pockets. “How about him?” she said. They looked at me. Why me?

“Just ask him,” she said, and they all piped up in agreement.

He seemed harmless enough. As I walked over to him, it occurred to me he might not even speak English.

“Excuse me,” I said.

He pulled his hands out of his pockets and looked at me. He was—how shall I put it?—a breathing Charioteer. “Hello,” he said.

“Um, my friends and I were wondering if you could tell us where we might find a place to eat.” I pointed to the clump of girls.

He glanced over at them. “I’m Demetri,” he said to me with a thick Greek accent.

“Oh, hi. I’m Ann.” Then, for some reason, we shook hands like it was a formal occasion.

“I’m waiting on my friend,” he said, pointing to a guy on a pay phone. “We’re meeting a group for dinner. All of you can join us, if you like. It’s not far.”

I motioned the girls over.

When his friend hung up the phone, he found Demetri surrounded by four American girls. Man, what did you do? his look suggested, and Demetri smiled at him and shrugged.

The restaurant was packed with locals, pulsing with syrtaki music and Greek dancing. It wasn’t long after the rest of their friends arrived that the young women in the group began to ask what American “boys” were like, which I left to the others to explain, this being a complex subject for me at the moment. Demetri slid his chair toward mine and asked what I studied at school. “History,” I told him. He asked about my family, my life, what I thought of Greece. I discovered he attended the Ikaron School, Greece’s Air Force Academy. He had a younger brother. And ever since his parents divorced, his mother worried about him more.

Plates of pastitsio, moussaka, salad, bread, and feta went around the table while we talked, just the two of us, for what seemed like ho

urs. He was intelligent and polite with a quiet, intense way about him. He translated the lyrics of songs the band was playing, most of them about love—losing it or finding it—then held out his hand to me. An invitation to dance.

I looked at the dancers with their arms clamped on one another’s shoulders, at the complicated steps they performed, at the tables jammed with people watching and clapping. I felt myself sweating under my gray turtleneck. I’d been blending in fine at the table, a lot like the curtains hanging behind me. The girl who’d run like beach wind around the track in Olympia seemed like another person.

“I’ll teach you,” Demetri said. His hand still stretched out.

The great dancer Isadora Duncan, who was, coincidentally, deeply influenced by Greek myths, spoke of dance as a manifestation of the soul. I’d been dedicated to invisibility for such a long time that I did not dance, not in public or private. I did not want my soul out there expressing itself. Who knew what it would say?

Demetri leaned down, his mouth close to my ear. “Life is short.”

If you don’t dance with him, you’ll regret it. The line had been used on me so often, now I was using it on myself. Besides, if I was going to live the kind of life I wanted, I would have to be less like the draperies.

I took Demetri’s hand and he pulled me onto the dance floor. At some point, bouncing along in the Greek dance line, the thought of my ex-boyfriend popped into my head, accompanied by the dull pang that had followed his rejection. It had not completely gone away. I pictured myself boxing up the photographs of him that lined my desk and dresser back home. I told myself I would be okay.

We kept dancing, song after song, and when the other dancers climbed up on the tables, I was right in the middle of them. Finally, laughing and exhausted, Demetri and I slipped outside into the cool night air. He wrote his address on a piece of paper and handed it to me. I opened my eyes when he kissed me. The Acropolis was lit up just over his shoulder.

The Secret Life of Bees

The Secret Life of Bees The Invention of Wings

The Invention of Wings Traveling With Pomegranates

Traveling With Pomegranates The Dance of the Dissident Daughter

The Dance of the Dissident Daughter The Mermaid Chair

The Mermaid Chair The Book of Longings

The Book of Longings The Invention of Wings: A Novel

The Invention of Wings: A Novel The Invention of Wings: With Notes

The Invention of Wings: With Notes