- Home

- Sue Monk Kidd

Traveling With Pomegranates Page 4

Traveling With Pomegranates Read online

Page 4

After the Fun Girls and I got back to the hotel, I was too excited to go to bed. I persuaded one of them to go up to the rooftop, where we waited for the sun to come up. We watched as light spilled over the city of Athens.

The next night Demetri met me in the lobby of my hotel. We walked for blocks, and when we got back, I was surprised when he gave me a necklace, a simple chain with a blue stone. He’d gone out and bought it earlier that day. To remember him by. We promised to write and said good-bye. The last thing he said to me was, “Ann, learn some Greek.”

Once I was back home in South Carolina, Demetri and I exchanged letters. I bought Greek language tapes and listened to them in my Toyota Corolla, practicing phrases like Pou einai i toualeta? (Where’s the toilet?) The word I loved the most was kefi. It means joyous abandonment.

My plans for the future took on weight and detail. I pictured myself with a doctorate, teaching Greek history, writing during sabbaticals, and continuing my studies in Greece, maybe even working there. My parents and friends encouraged me. I applied to the master’s program in history at the University of South Carolina, the one affordable place I knew that had a program with an emphasis on the ancient world, including Greece.

Two months after my return from Greece, not long before my senior year, I met Scott. I spotted him in a pizza place near campus. A recent graduate of the University of South Carolina, he sat at a table with a group of friends. He looked familiar.

Wearing a maroon Carolina baseball cap, he had a handsome, tanned face, brown hair, and blue eyes that were glued to a golf tournament playing on a television set over the bar. Somebody missed a putt and he groaned. In an act of boldness that was so unlike me I can only attribute it to Greece, I walked up to him.

“I think we went to the same high school,” I said.

He stared at me, squinting a little. Clearly, I did not look familiar to him. “I’m Ann. Ann Kidd.” I wished I had not said my name like James Bond.

“What was your last name?” he asked.

“K-I-D-D.” I readied myself for the questions that always followed: Any relation to Captain Kidd?

No.

Billy the Kid?

But he didn’t ask me either of those.

“Any relation to Bob Kidd?” he said.

“He’s my brother.”

Scott smiled. “Bob and I played Little League together on the Perk’s Car Wash team.”

We’d grown up in the same town.

I sat down and we talked baseball. I think it surprised him that I could talk baseball. More so, that I wanted to. I told him I owned a baseball signed by Hank Aaron and that I’d watched the Braves play the ’95 World Series alone in my dorm room and called—who else but—Bob when they won.

On our first date we almost went to a Bombers (Columbia’s minor league team) game, but due to extreme hunger, we ended up at an Italian restaurant called Mangia, Mangia, which roughly translates as Eat, Eat. We’ve been dating ever since.

Scott’s degree was in sports administration—he was a brilliant tennis player, a golfer, a surfer, and stored baseball statistics in his vault of a brain—but his day job was in real estate. He had an outgoing, affable nature—he could sell ocean water on the beach if he wanted to—but in private, his warmth and openness was just as real. I learned quickly that he was a grounded, dependable person I could count on, but he also had an independent way of viewing the world—not conforming to conventional ways of thinking, but making up his own mind. He was both a people person and his own person—the perfect combination. I loved how much he cared about his interests and how hard he worked to achieve his goals and the running stream of wisecracks that always made me laugh. I fell hard for him.

As my relationship with Scott developed, I sometimes thought about the tiny offering I left at Athena’s temple in Delphi and the words I told myself: Don’t ever lose yourself again. And I was vigilant. If I wanted to browse a bookstore or walk the beach instead of watching his tennis match, I did. I realized that not losing myself wasn’t only about how we spent time, though; it was about the way I valued myself within the relationship. I felt I’d left the accommodating girlfriend role behind. I had only to look at Athena’s face on my ring to be reminded to keep it that way.

When Mom called and asked if I wanted to go to Greece with her, it was early spring and I was in the thick of my senior midterm exams, my future seemingly locked in place. I’d missed Greece from the moment I’d left. There were times I wondered if I could possibly wait years and years to go back.

“Really? Seriously??” I shouted into the receiver.

Mom said we were going there to celebrate her fiftieth birthday and my graduation. A celebration. No problem.

I called Scott with the news. He showed up an hour later holding a plastic grocery bag. Inside was a jar of Greek Kalamata olives.

Curled up on my sofa a few weeks later, I opened a letter from the University of South Carolina, informing me that I’d been rejected from the graduate program to study ancient Greek history.

At the time I lived alone in a one-bedroom apartment after Laura moved to pursue her studies in Charleston, and I could have wailed if I’d wanted and no one would have heard, but I couldn’t muster anything so forceful. Everything drained out of me. I stared at the television, which was not on. I stayed like that for a while, then folded the letter back into its creases. I slipped it into the back of a drawer, covering it with gym socks and underwear. I told no one.

In the weeks that followed, the drawer became a receptacle of so much hurt and disappointment, I couldn’t walk past it without my eyes welling up. I fell into what I can only describe as despair. It simply had not occurred to me that I wouldn’t be accepted. I had the grade point average, a decent list of extracurricular activities, all the bells and whistles you supposedly need. I probably didn’t dazzle anybody with my GRE score, but still, it wasn’t that bad. I’d figured that, if nothing else, the sheer force of my wanting would get me in.

It took me two days to tell Scott, two days throughout which he kept asking if I was okay.

Finally I just said it. “I didn’t get in.”

“You didn’t get in? You mean, to graduate school?” He was shocked and upset. I wished he would just do the water-off-a-duck’s-back thing that he was so good at and go back to watching The X-Files. He was usually so laid-back, but suddenly he was riled up, determined to peel the lid off my feelings.

“They’re crazy,” he yelled. “You need to call them.”

“And say what?”

“That they made a mistake.”

He could not be serious.

“It happens, okay? I’m fine.”

But it was not okay and I was not fine, and worse, I feared the school was not crazy, that they knew exactly what they were doing.

I had the benefit of telling Mom over the phone, adding that it was not that big a deal, trying to downplay my embarrassment.

How could she and Dad not interpret the letter the same way I had—as an official pronouncement that I was not academic material, not bright enough, not good enough? Of course, my parents refuted that, but somehow their reassurance made me feel even more ashamed. I decided I did not want to talk about it. Ever.

After I was accepted into the graduate program in history at the College of Charleston, my precautionary “backup” school, I decided to go, not out of desire, but out of duty and desperation. My emphasis would be American history. I told myself it was my best and last option.

Once again, I called Mom, this time to tell her I was moving to Charleston. I tried to sound excited about graduate school, then steered the conversation to the news flash that we would be living in the same city.

“What about Scott?” she asked.

“He’s moving to Charleston, too. He’s already looking for a job.”

“Things are pretty serious then.”

“They are,” I told her, keeping it short and to the point. We’d been together almost a year.

We simply did not want to be apart.

It seemed strange that my pain about the rejection letter and my happiness with Scott could exist inside of me at the same time. He observed my sadness, and his willingness to allow my feelings made me care for him more. There was never the unspoken question: aren’t I enough to offset those feelings? He seemed to understand they came from another part of me.

Graduation came and went. I found an apartment in Charleston. With three months left before the fall semester started, I spent my mornings slumped in a lawn chair on the beach, skimming the classifieds for a part-time job. Inevitably, I ended up anchoring the newspaper under my chair and staring blankly at the water, wanting to tuck myself away where life could not find me again. I observed flotsam on the ocean and fantasized about floating off with it.

What happened should not have thrown me like this, I reasoned. Nevertheless, instead of dissipating, the pain had grown, solidifying itself around the rejection letter. I’d never been depressed before and I didn’t quite understand what was happening to me. I told myself a thousand times to get over it, to regroup, but the sadness became intractable, eventually accompanied by anger at the turn my life had taken. It was odd how abandoned I felt by the future, by my own self, by the promise of the life I’d discovered in Greece. I was not proud of any of this, how things had imploded, the way depression had taken over, how I’d retreated. My world became an unforgiving place. It scared the daylights out of me.

I feel like a failure, I wrote in my journal. I was twenty-two.

Luckily, I got a job as a part-time assistant to the editor of Skirt!, a local women’s magazine, which I gathered would mostly involve answering the phone and being the all-round gofer girl, a position I would begin when I returned from Greece. When I left the interview, I stopped in the salon next door and made an appointment for a haircut. A week later, in what may have been a small act of grief or a reach for newness, or maybe both, I had my long hair cut off. When Mom and I left for Greece, I looked like Tinkerbell.

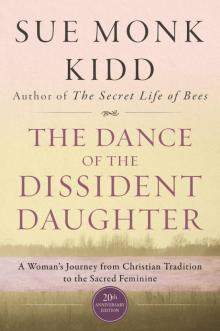

Now, here in Neverland, sitting beside the Parthenon on the same slab of marble as before, I spot my mom in the distance. She stands by the Erechtheion, taking pictures of the sculpted columns of women on the Porch of the Caryatids. She wrote about the Caryatids in her book The Dance of the Dissident Daughter. She described them as an embodiment of “strong women bearing up.” Women who bear the weight of opposition, she wrote, create a shelter for the rest of us.

The Dance of the Dissident Daughter was published during my sophomore year in college. When I opened it and saw it was dedicated to me, I read it like a mother’s letter to her daughter, sometimes forgetting her story was being read by thousands of other people. At times it seemed beyond weird that we’d lived in the same house during those years—I’d known so little about what she’d struggled with inside. There had been hints—bits of conversation, the piles of feminist theology books that were suddenly in the house, moments when it was apparent some kind of awakening or ripening was going on in her. Mostly, though, I knew her as my mother—the one who stayed up half the night decorating my Raggedy Ann birthday cake, who indulged me by creating the Coke/ Pepsi Challenge in the kitchen for Bob and me, who helped me pick out my black cotillion dress, who taught me how to parallel park at the DMV—but when I finished Dissident Daughter, I glimpsed her, for the first time, as a woman, like one of those beautiful Caryatids she’s standing with now.

Catching my eye, she waves and begins to wind her way toward me through the other tourists. I wonder why I can’t tell her what I’m going through. When it came to the letter back home, still in the drawer with my gym socks (why did I keep it, this evidence against myself?), certainly I didn’t think she’d reject me. Perhaps the shame of failing is not my only reason for not talking to her about it. We’ve been close since childhood, but I feel a kind of partition between us now, not anger or aloofness, but a room divider that properly marks the space: this is your territory, this is mine. I did not confide intensely personal matters to her. Are the particulars of your own darkness something you describe to your mother or your best friend?

But it wasn’t just the darkness I secreted, was it? Why did I give her only the postcard version of my first trip to Greece? Ran a race in Olympia, visited Athena’s Tholos, saw the Charioteer, sat beside Parthenon, danced in a restaurant with some locals, bought a pretty ring . . . having a great time—wish you were here. Obviously she knew I’d been affected enough to want to spend my life teaching ancient Greek history, but I’d left her to sense for herself the deeper imprint those experiences had made on me. Maybe it was the particulars of my soul—the experiences, feelings, and inner thoughts I held close—that I kept from her.

As I sit here, I feel the depression closing in.

“Help me,” I pray, barely moving my lips.

I suppose I sought out this spot again in the hope I would have a revelation, like before—that lightning would strike twice and I would know what to do with my life. Or, that something inside of me would get completely rearranged and my depression would evaporate.

None of this happens.

The last thing I want is to seem ungrateful or make my mother feel like bringing me here was a mistake. How can I possibly tell her the whole trip feels mournful? And if I do tell her that, how can I possibly expect her to believe the other side of that truth—that there is nowhere else I’d rather be.

“Let me take your picture,” Mom says. She focuses the camera. Click. I already know I’ll put the photo on my dresser and compare it to the one that was taken of me on this spot the year before, the one in which I am grinning with abandon while massive chalky columns beam up behind my head.

I’m afraid of becoming invisible again.

We walk in a dusty loop around the Parthenon toward the Acropolis Museum. There is a sculpture relief inside I want to see called the Mourning Athena. In it, Athena holds her spear upright with her head bent against it as if she’s mourning. The other name for the relief is Contemplating Athena. When I saw the image in a book, though, Athena did not appear to be in deep thought. To me, she appeared to be grieving, like the fight had gone out of her.

The museum, we discover, is closed for renovation. I stare at the notice on the door, twisting the Athena ring on my finger.

“Next time,” we joke.

Mom glances at her watch. “Ready to go?”

I nod and suddenly my eyes fill with tears.

“Ann?” Mom says. “What is it? Are you okay?”

“It’s—it’s just my hair,” I say, putting one hand on the back of my bare neck and managing a smile. “I miss it.”

Sue

The Cathedral of Athens

Ann and I wander through the Plaka, threading the convoluted tangle of shops and restaurants. The streets twist and coil, occasionally doubling back on themselves. I realize we’re lost the third time we pass the bearded young Orthodox priest in black robes standing outside a jewelry store.

“If we loop by him one more time, he’s going to think we’re stalking him,” Ann says.

I smile. Like her brother, she has always been funny, cracking us up with her wry observations. It’s a relief to hear her making a joke. Earlier today on the Acropolis she had been distant and pulled into herself, even tearing up for a moment when we left. As we walked down the path the word depression came to me for the first time. Could she be . . . depressed? I pushed the thought away. But now as we move through the narrow, stone streets of the Plaka, the word darts again at the edge of my thoughts. Depression.

A corkscrew of alarm twists in my abdomen. I have a ferocious urge to swoop in like a mother hen, gather Ann under my flapping wing, and say, Look, I’m not oblivious. I’m your mother. Something’s wrong. Talk to me. Let me fix it. But I know my impulse to tear open the closed, secret place in my daughter comes from a need to stave off my own fear. When is the impulse to help an adult child a wise intervention and when is it self-serving and prying? I have an uneasy feeling I wil

l have to carry the question around for a while like some grating pebble in my shoe.

I tell myself Ann is a young woman who needs to find a separate sense of herself in the world, who’s trying to stand fully in her own life. Let it be. For now.

As we pause before a shop window, a cluster of shining red baubles catches my eye. No, not baubles—what are they? Leaning closer, squinting into the glare, I realize I’m looking at glass pomegranates. They’re piled like ruby eggs into a nest of twigs. “Look,” I say.

“They’re in a bird’s nest,” says Ann.

It appears to be a real one. I imagine the shop owner finding the nest on a limb in her garden and thinking: Oh, perfect for displaying pomegranates!

I think of Persephone eating the fruit in the underworld. How the flesh splits open to reveal a small, secret womb and the seeds spill out like garnets.

The door to the shop is locked. Closed for lunch. Ann and I cast one last look at the pomegranates and walk on, famished now, ready to find our way out of the maze. After consulting several shopkeepers—one of whom follows us to the door holding a plaster-cast statue of Poseidon, cajoling, “You buy, yes?”—we emerge into a familiar, open square that buzzes with tourists, spared another lap around the priest.

We slip into an outdoor taverna and are barely seated when two scrawny cats appear and stare at us with pleading eyes. They lick their paws like they’ve sized us up perfectly and are preparing for a banquet. “So what would the cats like us to order?” I ask.

“Kotopoulo. Or psaria,” says Ann, then translates: “Chicken. Or fish.”

She has been studying Greek. It began over a year ago after her college trip. She came back full of purpose, with a plan to teach ancient Greek history. You couldn’t have missed the new vividness about her, as if being over here had flipped on a light inside of her that no one had quite noticed was off. Before the trip, her own pursuits had seemed overshadowed by her relationship with her boyfriend, a subtle eclipse I noticed only in retrospect. Even Sandy, a professional counselor, didn’t have a name for what had happened to her in Greece. “She seems to have ‘found herself,’” he remarked. And this “finding” had not faded, not for all this time. Until now.

The Secret Life of Bees

The Secret Life of Bees The Invention of Wings

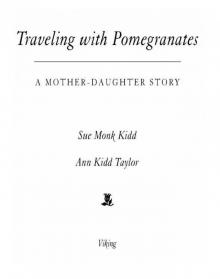

The Invention of Wings Traveling With Pomegranates

Traveling With Pomegranates The Dance of the Dissident Daughter

The Dance of the Dissident Daughter The Mermaid Chair

The Mermaid Chair The Book of Longings

The Book of Longings The Invention of Wings: A Novel

The Invention of Wings: A Novel The Invention of Wings: With Notes

The Invention of Wings: With Notes